Whiskey barrel chocolate: A case study in flavor (Part 2)

Co-written by Aaron Prater, Chef: Professor, JCCC School of Culinary Education

Read Part 1 of this article.

The experiment required the use of a chamber vacuum machine, often used for marinating meats, a FreeZone® -105° Freeze Dryer and a Shell Freezer. During maceration, the whiskey was forced into the barrel staves under vacuum, and the staves and liquid were then sealed in bags for further infusion. After sitting several days, the liquid was then poured into flasks and pre-frozen at -50°C for lyophilization. During lyophilization, liquid from solid state (ice) is removed in gaseous form, thereby bypassing the liquid phase. The samples were lyophilized and the extracted flavor was given to Elbow, who added the freeze-dried powder to a chocolate bar. The result? A one-of-a-kind delicacy.

The experiment required the use of a chamber vacuum machine, often used for marinating meats, a FreeZone® -105° Freeze Dryer and a Shell Freezer. During maceration, the whiskey was forced into the barrel staves under vacuum, and the staves and liquid were then sealed in bags for further infusion. After sitting several days, the liquid was then poured into flasks and pre-frozen at -50°C for lyophilization. During lyophilization, liquid from solid state (ice) is removed in gaseous form, thereby bypassing the liquid phase. The samples were lyophilized and the extracted flavor was given to Elbow, who added the freeze-dried powder to a chocolate bar. The result? A one-of-a-kind delicacy.

The following is a brief overview of the procedure used by the team:

- Obtain whiskey barrel staves (See Figure 1)

- Place staves into maceration machine to force whiskey into pores using vacuum

- Vacuum seal staves with water and alcohol mixture

- Prepare and pre-freeze sample for lyophilization process (See Figure 2)

- Lyophilize sample to extract flavor of charred oak whiskey barrels in powder form (See Figure 3)

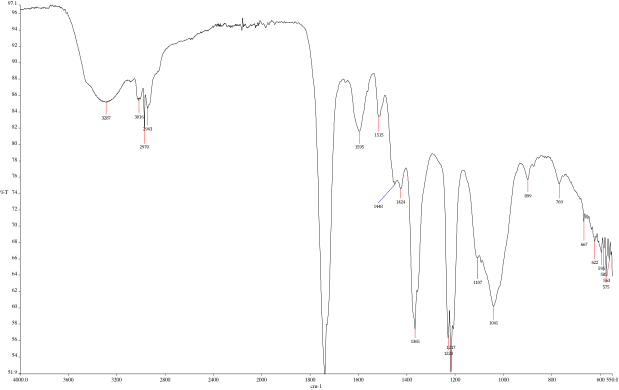

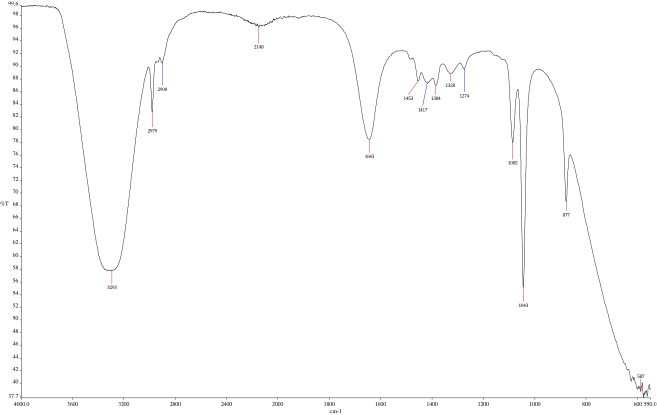

- Ensure quality of product by reviewing spectra (See Figures 4 and 5)

- Add flavor into chocolate bar

|

Figure 3:

|

Lyophilizing Whiskey Barrel Staves |

|||

|

Run |

Solvent |

Description |

Notes |

|

1 |

Whiskey |

2 Samples of 100 ml each into 600 ml water |

1 L resulted in 460 ml (200 ml for freeze dryer) |

|

2 |

†Everclear® |

Sample 1: 250 ml in 1 L |

1.5 L resulted in 650 ml; required further dilution to 5% |

|

|

|

Sample 2: 250 ml in 1 L |

Required further dilution to 5% |

|

|

|

Sample 3: 150 ml in 1 L |

Required further dilution to 5% |

|

3 |

10% Whiskey |

Test in progress |

|

|

|

100% Water |

Test in progress |

|

Step Three: Troubleshoot and Measure Results

Finding the most efficient way to obtain the pure flavor using lyophilization was a trial and error process. For example, the team modified sizes of the staves—or pieces of wood from the whiskey barrel—to achieve a large surface area for the flavor extraction to occur. In addition, they used varying amounts of water and different types of alcohols. Some solvents, such as a high-proof grain alcohol like Everclear®†, cost less and thus were more economical to utilize in the experiment. Using this potent solvent, though, lengthened the lyophilization process. It is a trade-off the chefs and experts at Labconco examined closely; eventually, after the troubleshooting process was complete, they decided against using that particular alcohol for future runs.

"In the end, we lose the liquids but keep the flavor compounds regardless of what we use," Williams, who conducted many of the lyophilization runs, explained. "The Everclear was a challenge because the high alcohol percentage required many dilutions before the sample was able to be frozen at -50°C and didn’t produce a higher yield." (See Figure 3)

To compare the flavors of the extracted charred oak whiskey barrel to the original whiskey, the group compared the spectra of the final products using a FTIR spectrophotometer. The peaks on the FTIR spectra show peaks at 1730 cm-1, 1036 cm-1, 912 cm-1, 706 cm-1, a broad peak at 1042 cm-1, and minor peaks in the lower sections below 600 cm-1.

"We believe these peaks represent a mixture of vanillin, syringaldehyde, coniferaldehyde, fallic acid and vanillic acid in varying quantities as well as other organic compounds. These compounds derive from the oak fibers of the whiskey barrel. The odor of these compounds is observed from the freeze dried samples, with vanillin being prevalent as well as coniferaldehyde, derived from a cinnamon molecule. Being solids at room temperature, it would make sense that these two compounds are present in the freeze-dried cake. When creating whiskeys, the flavors of vanillin, syringaldehyde, coniferaldehyde, fallic acid and vanillic acid are desirable. Metals are commonly found in whiskeys, and these can be seen in the minor peaks below 600," Goldstein said. (See Figures 4 and 5)

Using different concentrations of alcohol and water for the extraction should result in similar end products. Based on olfactory senses, the team found this to be true. They did, though, smell small variances from batch to batch. Given the different compounds, it was difficult to quantify the exact variances. According to the team, one improvement that might produce more quantitative results would be to run the samples through column fractionators before the FTIR analysis in the future. (At this initial evaluation of the process, that step has not yet been completed.)

"We knew exactly what we wanted on the final compounds," Goldstein, who has a chemistry background, said. "It is very important to be able to measure results of this in concrete terms."

-

To taste some delicious chocolate in person, get a personal glimpse of the extraction technique, and to improve your own lyophilization process development skills, attend the one-time-only class that resulted from this process, a very special Pittcon Short Course in New Orleans.

|

|

-

To taste some delicious chocolate in person, get a personal glimpse of the extraction technique, and to improve your own lyophilization process development skills, attend the one-time-only class that resulted from this process, a very special Pittcon Short Course in New Orleans.

† Everclear® is a registered trademark of Luxco, Inc.

| chevron_left | Whiskey barrel chocolate: A case study in flavor (Part 1 of 2) | Articles | Keep microorganisms out of laboratory grade pure water | chevron_right |